Migrating from Jekyll to Hugo

I’ve been working on this website for a few years now.

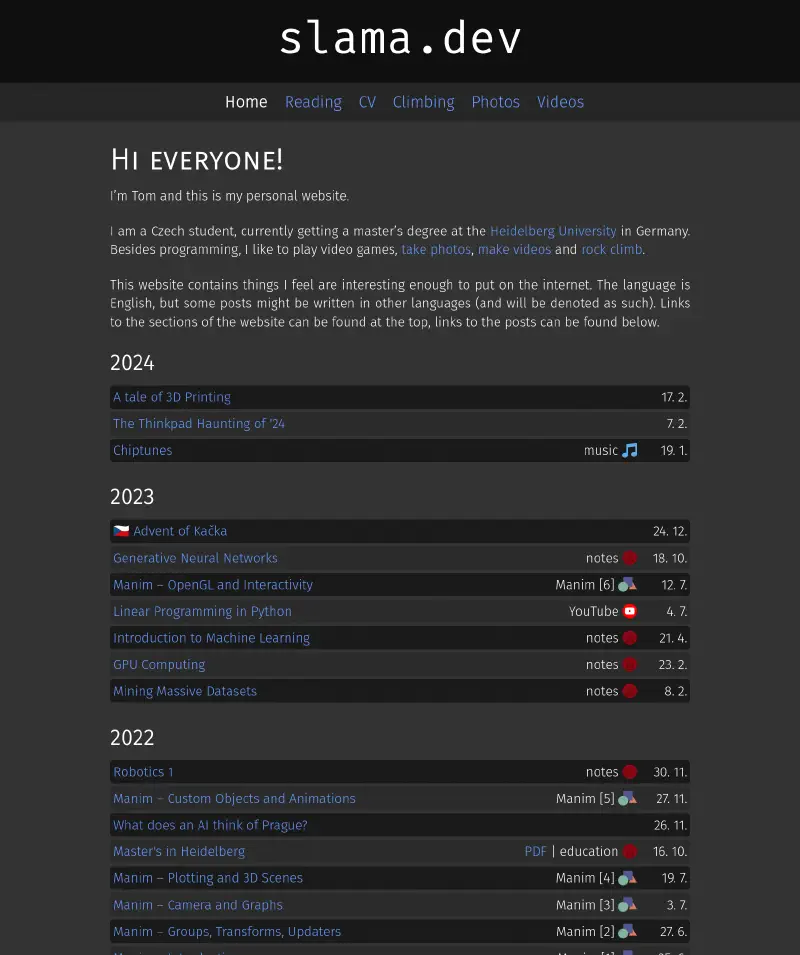

Looking at the Wayback machine, the oldest available snapshot is from 23. 10. 2019, which itself is not far off from the initial commit, which was 4. 5. 2019 – over 6 years ago.

Over time, I’ve added lecture notes (Czech/English), a climbing diary, some pretty neat photos, and much more. While I’m really happy with how the website grew, it was like building a ship as it’s sailing the ocean – add a sail here, patch the hull there, sprinkle some duct tape and hope it holds.

(2021 is missing since it’s not on wayback)

Although tech debt is something that could be addressed by refactoring the codebase, what could not be addressed are Jekyll (the SSG this website uses)’s terrible build times, the glacial pace of new updates, the lack of useful features like image transformations and overriding markdown to HTML conversions, and my personal dislike of Ruby (that one’s on me though).

Ultimately, I decided that a migration was warranted, and decided on Hugo since it’s fast, feature-rich, and in active development (although Zola, being written in Rust, was a very close second).

This post will mainly cover the changes that address the pain points that this blog developed over time, since that will be useful for both people interested in converting from Jekyll, and those that are interested in seeing what Hugo is about.

Let’s do some rewriting!

Build Times

This was arguably the biggest pain point for me when deciding to migrate from Jekyll, since work on an article meant taking a small coffee break to begin to see the rendered results. You could argue that seeing the article is not needed for writing the content, but this is absolutely not the case for me – I like to see how the paragraphs look, how the images align and how the code gets highlighted as I write.

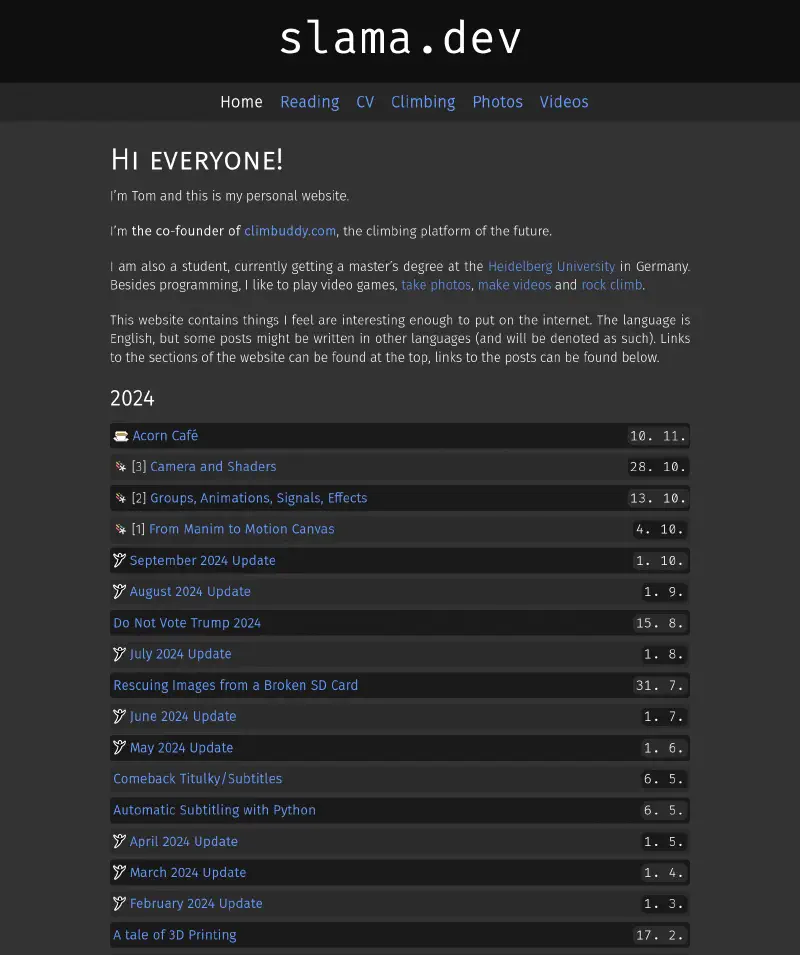

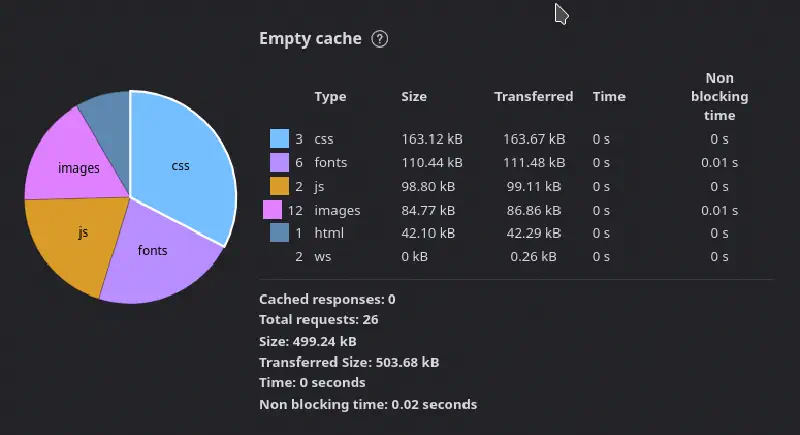

Cutting to the chase, here are the cold/hot build times for both the Jekyll and the Hugo version1.

4.9x / 20.6x speedup respectively. Cold build time occurs when the build folder is empty, while hot build time is every subsequent build.

I could further get the build time down to ~550 ms and thus achieve a 130x speedup when excluding climbing videos from the build (and linking them at the end), but I’d say the current state is more than good enough for regular development.

Page Bundles

As the introduction alludes to, the iterative way in which this blog developed meant that a lot of assets were placed where there was room for them – most were in /assets/<post_name>, some were just in /assets/, a few (especially climbing) were in /climbing, the cv.pdf was crying in the / corner… it was a mess.

While some of this is admittedly a personal skill issue, Jekyll does not make this any easier, as the /assets convention is the official way to store assets like images.

Hugo makes things much easier by using page bundles – the assets of a post can live in content/<post_name>/ and be referenced via a relative path, and things will just work.

This means that all of the post assets can be moved to where they belong, and structures like these

| |

with usage like  can be rewritten as

| |

and a nice relative path like .

This makes writing posts significantly easier, as you just plop the image in the given directory and reference it via a relative path – no careful typing of the absolute path necessary.

Image Processing

Working with images in Jekyll is absolutely atrocious.

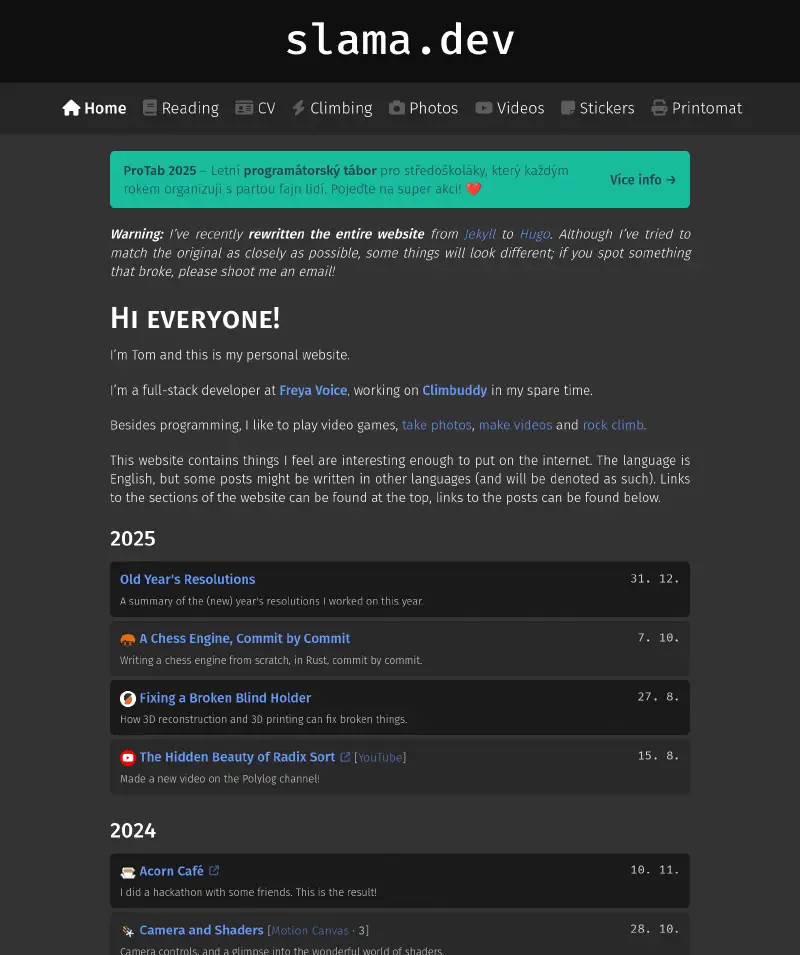

Besides the aforementioned path shenanigans, I try to keep my website relatively lean, clocking in at a little over 500 kB for the home page, which I think is reasonable in the current age of JavaScript monstrosities.

While this is easy to achieve for CSS/HTML-only pages, it becomes much harder when images get introduced into the picture (pun intended). The Jekyll version of the website handled this via a custom automated script that looked for images on the website and resized them, and another one that did something similar for the photo gallery.

This was unmaintainable.

Fortunately, Hugo has built-in image processing, which allows you to resize, crop, and manipulate images automatically.

This, in combination with a render hook that overwrites what HTML gets generated from Markdown’s  means that we can automatically convert and resize all images on the entire website without the need for custom scripts, with something as simple as this in the image render hook:

| |

Here is a nice blog post by Nathan Vaughn that goes into greater detail on how Hugo handles resources and some good practices, definitely recommend a read if you’re interested in implementing this on your own website.

A Subfonting Intermezzo

While writing the above section to boast about how fast my website is, I ran the test above and discovered, to my shock, that the website actually loads over 1 MB of data, with around 650 KB being fonts.

The reason for this is that the website uses 4 variants of Fira Sans (sans/code light/medium), and FontAwesome, which is notoriously fat.

But do we actually need all of the data the fonts contain?

Fonts include characters in a number of alphabets, most of which this latin website will never use, so we can discard them and only keep the relevant characters (in the case of FontAwesome, only the used icons).

We do this with pyftsubset (a part of fonttools), reducing the size to less than 100 KB (an 85% reduction)!

| |

Data Files

Although data files do exist in Jekyll, I didn’t make great use of them so I can’t blame this on Jekyll. Over time, however, I’ve added a few features to the website like my climbing diary, a photo gallery and even a hidden TBOI page, which are ripe for this feature.

Datafiles are exactly what the name suggests – files with data that can be used to generate the website. Many datatypes are supported, but this website uses YAML since it’s a good combination of human/machine readability.

As an example, the photos page is generated from a YAML file that looks like this:

| |

which is then used in generating the photos page as

| |

Tags vs. Shortcodes

Jekyll’s tags (plugins) are essentially Ruby function calls that return arbitrary HTML.

While this is awesome, since you can execute whatever code you want, it’s less awesome when you’re using someone else’s template, since they can also execute whatever code they want (unless you use --safe and disable plugins altogether, at which point Jekyll templating becomes cumbersome).

Shortcodes are Hugo’s way of doing templating, and they’re pretty nice, but this is the one thing that Jekyll does much better (at least for my case). Since I am the one writing this template, I’d sometimes like to just write some code instead of needing to contort the Go templates into things they shouldn’t do.

An example of this is the rewrite of the chess article highlight tag, which is a pretty ugly multi-pass shortcode that first adds invisible markers to starts/ends of things to highlight, and then does a second iteration to do the highlight.

Not too happy with that one, but this is a price to pay for security. If you really need Ruby-like tags, run a pre-processing script to generate the HTML of your choosing and then include it – not pretty, but functional.

Conclusion

I haven’t talked about asset minification, fingerprinting, menus, built-in KaTeX math support, and many other nice things that make using Hugo a much more pleasant experience than Jekyll, but I think I’ve shown enough to convince you that it really is.

I do want to say that Jekyll has community plugins that implement a lot of the functionality covered in this post, which is great on paper but all of the most popular plugins that I looked at were unmaintained (i.e. youngest commit is older than 2 years) – better to have a limited core implementation that’s maintained, than a rich plugin that’s not.

In the end, the rewrite went great – the website feels the same, the deployment is still a simple build + rsync (+ nginx restart for redirects to take place), and I can now focus on actual writing, instead of making more coffee since the build takes so long.

While page-level redirects were not necessary, file-level redirects were.

It turns out that people link assets from my website in other places, and since I moved most assets from /assets/<post>/... to /<post>/..., all of these would break.

To fix this, I wrote a small script to match files from old assets folder to the path in the new website, and these should now be functional 🙂.

To be fully transparent, the vast majority was done via Claude Code (no vibe, just supervision), as it was more laborious than interesting – a pinch of SED calls, a sprinkle of Ruby-to-Go-template rewrites, a few hours wasted on a bug in Hugo’s markdown parser… nothing out of the ordinary.

There were a few breaking changes that needed to be fixed, namely

- no

<div markdown="1">– this is honestly for my own good, because I completely abused this Kramdown-only feature when I should have been using tags, - broken code highlights due to Hugo’s different syntax highlighter – since Hugo uses Chroma, which generates different HTML structure/tags, a lot of highlighting on the website (not just code) broke; expected but annoying,

- things like the PDF generation were deprecated, since it was in a terrible state to begin with and the minor changes that those PDFs may receive in the future do not warrant another day spent on porting it to work with Hugo

I will now embark upon a crusade to convince my friends, many of whom I convinced to create a personal website in Jekyll, to switch to Hugo.

Wish me luck! ❤️

Technically, the Jekyll hot speed time was around 2.5 seconds if we run multiple builds in a row, but this doesn’t represent the actual use case – if we ever run a server in between (i.e. work on a post and want to see how it looks), the build goes back to ~71 seconds. ↩︎